Wall Street Journal article “Portfolio Rebalancing Might Be Overrated,” quoted an investment strategist as questioning the value of regular rebalancing. Although the author included many quotes from advocates of rebalancing, the article failed to explain the debate in a way that readers could understand, let alone judge, what was being said.

Wall Street Journal article “Portfolio Rebalancing Might Be Overrated,” quoted an investment strategist as questioning the value of regular rebalancing. Although the author included many quotes from advocates of rebalancing, the article failed to explain the debate in a way that readers could understand, let alone judge, what was being said.

Regular rebalancing is a key component of modern portfolio theory. It is important for us to provide the missing explanations here. Hopefully these clarifications will settle any debate about the value of rebalancing.

The article said:

To many, it is an unassailable principle: Investors should periodically rebalance their portfolios to their target mix of stocks, bonds, cash and alternatives that best suits their risk tolerance. Doing so is widely considered a best practice for reaching one’s long-term financial goals.

But some investing experts question that approach. Most recently, in an article published in Advisor Perspectives, Michael Edesess, chief investment strategist at Compendium Finance, suggests that rebalancing is no better or worse a strategy than buy-and-hold.

Each has advantages, depending on the circumstances, he says.

Any claims that rebalancing offers a bonus or excess return, compared with using a buy-and-hold strategy, “are mistaken,” Dr. Edesess, who is also a research associate at the Edhec-Risk Institute, said in an interview.

The premise is stated that rebalancing is a best practice for reaching one’s long-term financial goals. Then Michael Edesess is quoted as saying that rebalancing is no better than buy-and-hold at offering a bonus or excess return.

These statements are put as though they are contradictory, but they are not.

The historical expected return of bonds is about 3.0% over inflation and the historical expected return of stocks is about 6.5% over inflation. Any rebalancing between stocks and bonds will produce a lower return since on average you will be selling stocks because they have appreciated more and buying bonds because they have appreciated less. Rebalancing into cash produces an even lower return. (As for alternative investments — such as private equity, hedge funds, managed futures, real estate, commodities, and derivatives contracts — we do not recommend using most of these investments since often they are not publicly priced and traded.)

If mean return is your only measure of “best,” an asset allocation of 100% stocks would be best. Because of the difference in returns between stocks and bonds, they won’t rebalance themselves over time. Left to itself, the allocation to stocks will grow larger and larger until it represents close to 100% of your investments. As this happens, your portfolio will also grow more and more volatile, your expected mean returns higher, and your goals more susceptible to market corrections.

This wild volatility may threaten the fulfillment of your financial goals. Aiming for a 10% return with wild volatility doesn’t make sense if you only need a 7% return to guarantee meeting your financial goals. Sometimes slightly lowering your expected return can vastly lower your expected volatility. As a result, you increase the odds of exceeding the modest return you need to meet your goals. Rebalancing into stable investments can lower the volatility and provide a better chance of exceeding the minimum return which meets your longer-term needs.

In the article “Your Asset Allocation Should Be Priceless,” we demonstrated that when a portfolio is burdened with a withdrawal requirement, an all-stock portfolio may fail where an allocation to bonds would have succeeded. As we wrote, “There is an optimum allocation between stocks and bonds for a given withdrawal rate.”

For those who have a hard time understanding how an investment with a higher expected average return could result in a lower chance of success, consider an extremely profitable but extremely volatile investment. Consider an investment which one out of ten times adds to your $100 investment an additional $1,000, but the remaining nine out of ten times you lose everything. One out of ten times you make 1,000% and the remainder you lose everything. Your average mean return is a positive 100%. Meanwhile, your average median experience is to lose everything.

Having agreed that rebalancing into bonds or cash on average reduces your return even though it may increase your chance of meeting your long-term needs, let’s look at the effect of rebalancing between two allocations to stock. The article continues:

As support, Dr. Edesess cites research by himself and others that concludes that when two or more types of assets are present in a portfolio and the returns of those assets differ by only a small amount—which happens about two-thirds of the time, he adds—rebalancing will slightly outperform buy-and-hold.

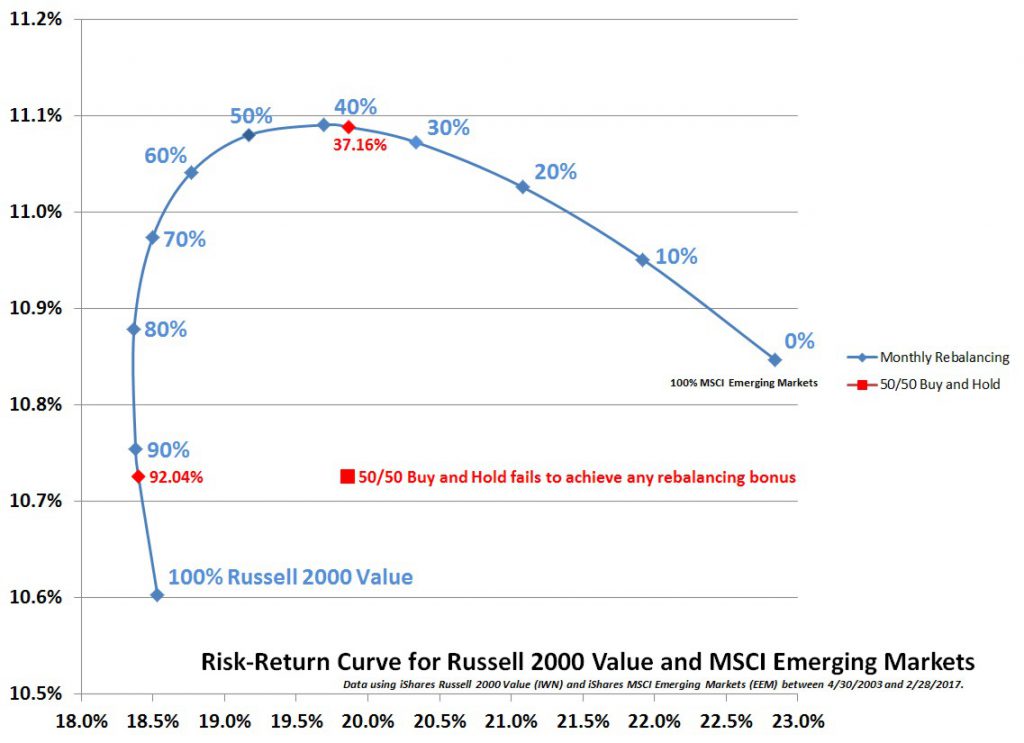

Take the example of the returns between 4/30/2003 and 2/28/2017 of portfolios built from iShares Russell 2000 Value ETF (IWN) and iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM).

Take the example of the returns between 4/30/2003 and 2/28/2017 of portfolios built from iShares Russell 2000 Value ETF (IWN) and iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM).

The mean returns differ by a small amount, only 0.25% (10.60% for IWN and 10.85% for EEM).

An initial 50/50 allocation which is never rebalanced would only have experienced a 10.73% annual return. Even after the near 14-years of market movement, this non-rebalanced portfolio still ends very close to its target 50/50 weight (with 50.76% in emerging markets and 49.24% in small-cap value) because the mean returns of the two funds are similar.

Meanwhile, an initial 50/50 allocation which is rebalanced monthly would have an annual return of 11.08%, 0.35% better. A portfolio which is rebalanced monthly would obviously end the 14-year experience equally weighted.

The monthly returns of these two investments had a correlation of 0.71. The lower the correlation the greater the rebalancing bonus.

Now, any regularly rebalanced allocation between 92.04% IWN and 37.16% IWN would have been superior to a 50% allocation to IWN which was never rebalanced. Returns would have been higher, volatility lower, or both.

Back to the article, Edesess finishes his thought:

But if their performance diverges by more than a small amount, Dr. Edesess says, “then buy-and-hold will greatly outperform rebalancing.”

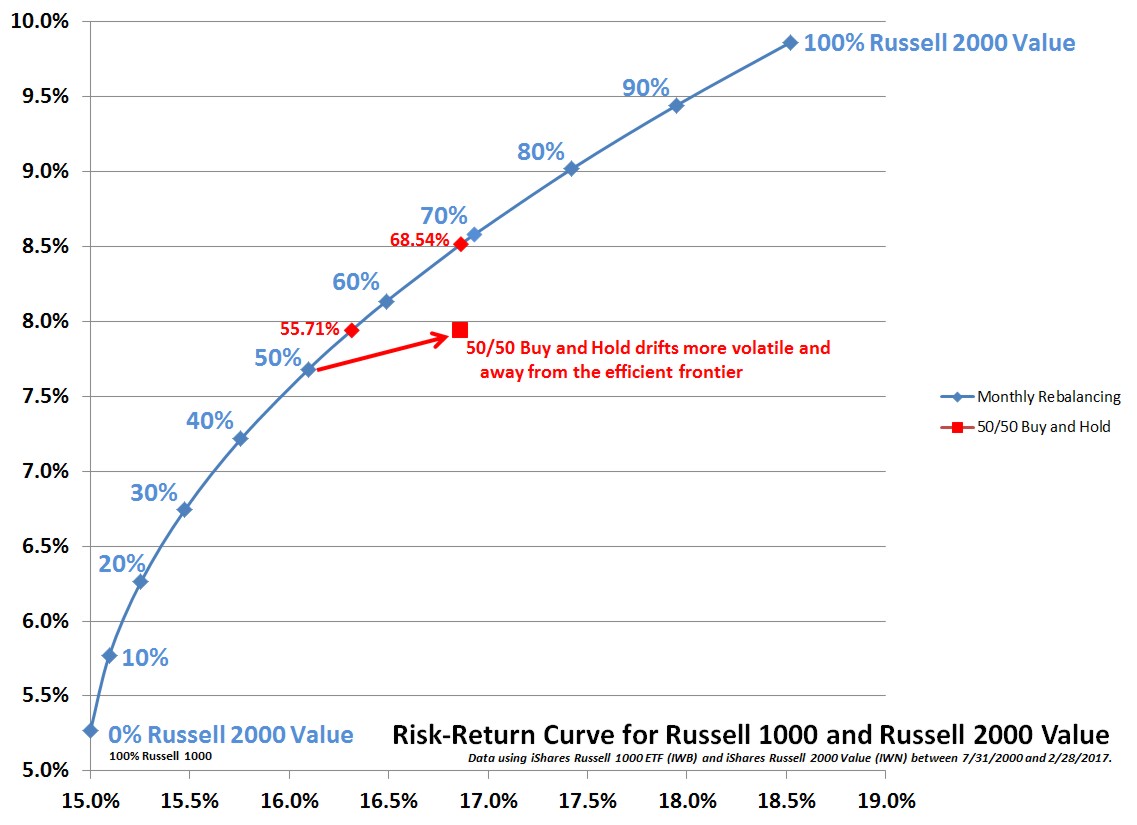

Take an example of the returns between 7/31/2000 and 2/28/2017 of portfolios built from iShares Russell 1000 ETF (IWB) and iShares Russell 2000 Value ETF (IWN).

Take an example of the returns between 7/31/2000 and 2/28/2017 of portfolios built from iShares Russell 1000 ETF (IWB) and iShares Russell 2000 Value ETF (IWN).

In this case, the mean return differs by a large 4.59% (5.27% for IWB and 9.86% for IWN).

An initial 50/50 allocation which was never rebalanced would only have experienced a 7.94% annual return. Because the mean returns of the two funds differ significantly, a non-rebalanced portfolio would have ended the 16.5 year experience with 66.98% in small-cap value and only 33.02% in large.

Meanwhile, a 50/50 allocation between the two funds rebalanced monthly would have resulted in a mean return of 7.68%, a 0.26% lower return. Again, the portfolio which is rebalanced monthly would end equally weighted.

Although the buy-and-hold strategy did not “greatly” outperform rebalancing, it did outperform. But it did so at the expense of becoming increasingly more aggressive in its asset allocation. A regularly rebalanced portfolio of 60% IWN would have had a higher mean return and a lower volatility. It would have been superior in both measurements.

Most of the remaining claims in the article are claims that can be summarized as, “If you let the asset allocation gradually grow more aggressive, then you will experience both a higher mean return and a higher volatility.” Having conceded that obvious point, I would counter that if you are willing to grow more aggressive, there is always an asset allocation which when rebalanced monthly would have a higher mean return and/or a lower volatility than a buy-and-hold strategy. Therefore the buy-and-hold strategy is not optimal. You have to look at the return you receive in light of the volatility risk you experience.

There are a few more statements in the article which, although not as critical to understanding the debate, nevertheless deserve explanation.

There are other skeptics about the wisdom of rebalancing as well. Michael Falk, a chartered financial analyst, author and partner at Focus Consulting, says rebalancing makes two false assumptions: One, that all securities are cyclical and regress to a mean. “Some securities fall and can’t get back up,” Mr. Falk says. And two, that all regressions to the mean take the same amount of time. “Hence, rebalancing cannot be assumed to always add value,” he concludes.

For the first assumption, I have written earlier that you should not necessarily rebalance at the sector level, let alone the individual security level. No advocate of rebalancing suggests rebalancing at the security level. If you tried to rebalance back into Enron, you would lose everything. In our article “The Complete Guide to Creating an Investment Plan,” we have written about the importance of defining your sectors in order to find a category that should have a persistent mean return. Having volatile non-correlated investment categories can boost the rebalancing bonus.

And no advocate of rebalancing assumes the second assumption. If you know which of the two asset classes is going to perform better over the next ten years, then you should put 100% of your portfolio in that category. If you don’t know, then setting an asset allocation based on getting the best return you can for the risk you want to take and then rebalancing regularly is a good strategy for uncertain markets.

The article does quote many financial professionals defending the math of asset allocation and rebalancing as well as making the point that if you want to drift aggressive, just set an aggressive asset allocation from the beginning and rebalance to that more aggressive allocation.

This comment was perhaps the strangest:

And still others aren’t fond of rebalancing for practical reasons. “Your money is like soap: The more you touch it, the less you have,” says Brent Burns, president of Asset Dedication in San Francisco, an asset manager for financial planners. “We set our tolerance bands very wide so that we do not have to rebalance very often, if ever.”

As you can see from both of the charts above, the rebalancing curve bows up and left. Rebalancing produces greater returns for less volatility. It isn’t clear how money is like soap. Perhaps that is true for brokers who charge exorbitant trading commissions or for obscure exchange-traded funds with large bid-ask spreads, but for advisors using the many no-transaction fee ETFs or a low cost broker like Schwab, TD Ameritrade, or Fidelity, the trading costs and bid-ask spreads are negligible compared to the expected rebalancing bonus. Capital gains management is important, but there the hurdle rates for realizing capital gains are often lower than the expected excess return from rebalancing.

The final comments make it clear that Edesess is attacking the idea that rebalancing into bonds can boost returns. But this is an idea that no one believes.

The risk that should really matter to investors, says Dr. Edesess, is long-term: the risk that in 30 or 50 years they may have insufficient savings. But what advisers typically focus on, he says, is short-term risk. This is a problem made worse, he says, by the risk-tolerance questionnaires that advisers ask their clients to fill out. The questions mostly focus on investors’ tolerance for short-term volatility, he says. The answers are then used to determine the desired target allocation for the portfolio.

“As a result, investors’ risk posture is judged as a function of their attitude toward short-term volatility,” he says. “To then compound the error of regarding that as the investor’s risk profile by trying to re-establish it in every time period makes even less sense.”

We agree that your bond allocation should have little to do with your emotional attitude toward risk and instead have everything to do with the withdrawal rate that the portfolio has to endure for the next five to seven years. We also agree that investors underestimate the danger of inflation and overestimate the danger of short-term volatility. But regular rebalancing actually moves money from bonds into stocks when the markets are down rather than leaving a greater percentage in stocks just because the markets are up.

If I made the best case for Dr. Edesess’ position, I would argue it this way: Most people set an asset allocation which is too conservative. They put too much in bonds. And then to make matters worse, they rebalance back to their 50/50 or 60/40 portfolios too quickly. It would be better for them not to rebalance. It would be better for them to drift more aggressive because they should always have been more aggressive. And this more aggressive portfolio will, over time, produce better results.

My counter argument would be: Yes, most people set an asset allocation which is too conservative. The commission-based financial services industry may do this simply because they don’t want to lose clients and clients don’t fire their investment advisor when the markets are up and when the markets are down, the more conservative portfolio won’t be down as much as everyone else. But for fee-only fiduciaries, we should simply educate our clients not to fear short-term volatility and fear inflation instead. We should give them the appropriate asset allocation from the start, tuned to give them the best chance of meeting their financial goals. And then we should rebalance them regularly in order to keep them tuned to give them the best chance of meeting their financial goals.

Finally, although rebalancing between stocks and bonds will not boost returns, rebalancing between stock categories can and often does boost returns.

Photo by Gabriel Sanchez on Unsplash