John Blood has a nice article in Investment Advisor magazine entitled “Factor Investing: A Post-Modern Portfolio Theory

.”

John Blood has a nice article in Investment Advisor magazine entitled “Factor Investing: A Post-Modern Portfolio Theory

.”

Factor investing “tweaks the idea of asset allocation and diversification by seeking out types of securities that have been shown, by decades of academic research, to offer positive return premiums over time.” The article goes on to explain:

In the 1960s, Nobel Laureate Eugene Fama’s research showed that a portfolio of selected stocks won’t typically beat the broad market index. Factor research looks further, dissecting alpha to understand the elements of successful stock picking. It turned out that outperforming stocks share certain traits, which were given the name factors.

There are literally hundreds of potential factors that have been identified, but academic research has helped narrow the field by identifying those that seem to have the greatest probability of minimizing risk while maximizing returns.

Identifying factors which outperform the market is not the same as traditional active management nor is it market timing. Active management seeks to analyze individual companies in order to try to predict which company’s stock will outperform the market over a short time horizon. Factor investing weights stocks based on a single easy-to-measure factor regardless of market timing. As Blood explains, “Factors are observable and quantifiable security-level characteristics that can explain differences in stock returns.”

We analyzed some of the factors of investing in our series on “The Efficient Frontier of Investing” which includes an analysis of “Size, the Second Factor of Investing.”

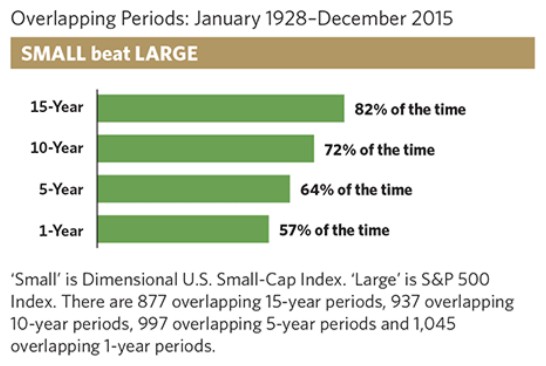

Size is measured by a stock’s total capitalization. Over time, small-cap will outperform large-cap even after factoring out measurements of volatility.

Blood’s article included this analysis of the historical performance of the size factor premium over rolling periods:

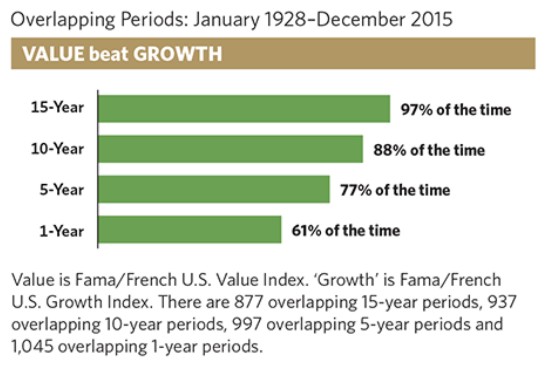

And here is a similar chart for how frequently value stocks beat growth stocks:

Factors such as size and valuation are a critically important part of portfolio construction. Again, from Blood’s article:

Numerous economists have demonstrated that, over the long term, returns of an equity portfolio can be explained almost entirely through a factor lens.

Columbia University finance professor Andrew Ang, author of “Asset Management: A Systematic Approach to Factor Investing,” uses an insightful analogy: Factors are to investment assets as nutrients are to food. Much as we eat foods for their underlying nutrients — meat or soybeans for protein, nuts for healthy oils, fruits and vegetables for vitamins and fiber — to the quantitative investment manager it is investment factors that really matter, not the assets themselves. Just as foods are bundles of nutrients, securities are bundles of factors.

We have described in other series the process of portfolio construction including the step of defining which sectors to invest in and crafting the asset allocation within your asset allocation.

Even when you believe in index investing, there are thousands of different indices. And the most common stock market indices (The S&P 500, The Dow, and The NASDAQ) are all US large-cap stock indices which do not represent the movements of small- and mid-cap stocks, let alone a diversified global portfolio. Factor investing would suggest constructing a portfolio which is very different from the S&P 500.

And once you have identified a factor, you still have to determine if there is a low cost method of investing in that index. The cost of investing, also known as the expense ratio of the fund, has to be small in comparison to the expected boosted performance from that factor. If, for example, small-cap value is expected to outperform the S&P 500 by 2.12% annually, the fund you use for small-cap value investing should not have an abnormally high expense ratio. The additional expense ratio should be a small fraction of the additional expected return. Since specific funds are the method by which you will experience investing in a factor, security selection is important. As Blood writes in the article:

Because the approach is more strategy-based than product-based, advisors can select the least expensive, most efficient product that delivers consistent exposure to the chosen attribute.

One excellent fund which can be used for a small-cap value allocation is the Vanguard Small-Cap Value ETF (VBR). It has an expense ratio of just 0.08% compared to the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO) with an expense ratio of just 0.05%.

As you can see from the chart above, small cap-value will not out perform every decade, but over the past decade it has. As of 10/31/2016, VBR has an annualized 10-year return of 6.81% versus VOO/VFINX’s annualized 10-year return of 6.58%. This has been true even during a decade when dynamic asset allocation factors using forward P/E ratios would frequently have suggested tilting more towards large-cap and growth.

During other time periods the small and value factors have averaged even larger premiums.

During the 2000-2002 slide in technology stocks, the returns of large-cap growth and small-cap value were very different. In 2000 while large-cap growth stocks lost -33.51, small-cap value stocks gained an impressive 13.65%. In 2001 while large-cap growth stocks lost an additional -29.07%, small-cap value stocks gained an additional 18.58%. It wasn’t until 2002 when large-cap growth stocks lost -33.15% that small-cap value stocks finally dropped a relatively mild -8.42%.

Had you been invested in large-cap growth stocks during 2000, 2001, and 2002, you would have lost -68.47% of your value over those three years. Meanwhile, if you had been invested in small-cap value stocks during that same time period your investment would have appreciated 29.10%.

Despite better average returns, factor investing can’t predict which decades the factors will boost returns and which they will not.

It is similar to a master at the card game of bridge knowing that the odds favor a king being on one side of the board and finessing accordingly. He may be wrong 25% of the time but finessing according to the odds is the right strategy 100% of the time. Even when the finesse goes against you, it is unfortunate, but still not a mistake. Again from the article:

One of the key tenets of factor investing is that you can’t time the factors. Factor investing is a long-term approach. Over long periods of time, our expectation is that value will beat growth and small caps will beat large caps. What’s out of favor today will come back at some point in the future.

Some investors would consider factor investing an active approach, and we would not quibble over semantics. What it does do, however, is remove the “human” element of trying to guess, predict or forecast what the future holds for the market, asset classes or individual securities. That process is replaced by one based on rigorous academic discipline, where investment decisions are driven by empirical evidence and probabilities that have been arduously tested by economic and financial thought leaders. The approach is systematic, strategic and unemotional. The factors don’t change based on today’s news or the latest research report from a Wall Street firm.

Factor investing ignores the daily financial news in favor of decisions based on empirical factors supporting a long-term investment strategy. While financial news focuses on narratives and is subject to the narrative fallacy, factor investing requires long periods of time to be proven to be the best strategy.

Sticking to these factors and rebalancing back into the categories which have gone down provides the best method for maximizing long-term returns.

Photo used under Creative Commons Zero license.