Two critical questions were raised during the first presidential debate: Are small businesses important to American’s prosperity? And if they are, which candidate will unleash that engine of economic growth and employment? Fact-checking the candidates offers a clear answer.

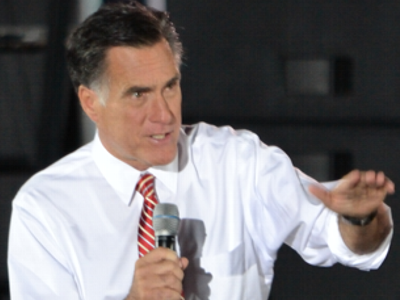

Romney began by claiming that “54 percent of America’s workers work in businesses that are taxed not at the corporate tax rate, but at the individual tax rate.” This was how he justified lowering the top marginal tax rate even if we eliminated deductions and exemptions and collected the same amount of tax.

I’ve argued before that effective tax is irrelevant. All economic decisions are made at the margin. So it makes sense to lower the top marginal rate even if you have to eliminate deductions to collect the same effective tax rate. If there was one economic principle I wish voters understood, this would be it.

Karen Mill, head of the Small Business Administration (SBA), said two of every three new jobs in this country are created by small businesses. And she said that more than half of Americans either own or work for a small business. In the same speech she announced 17 tax breaks for small businesses via the Recovery Act, the Small Business Jobs Act and other laws in the spring of 2011.

Obama made use of these tax breaks in the debate, claiming, “I also lowered taxes for small businesses 18 times.”

If you are a small business owner like me, you cannot remember even one time Obama lowered taxes. He is including a plethora of small short-term tax incentives, many of which have already expired. For one year I could hire an employee and pay a pittance less on employer Social Security. For a brief time I could, if my tax rate had been lower, only pay 90% of what I owe in quarterly tax payments to avoid penalties and interest at the end of the year. Now my rate is 110%.

My employees can deduct the cost of their health insurance as a pretax deduction. For one year small business owners were also allowed this tax deduction. Now we must pay for our own health insurance with after-tax dollars. One year tax credits were able to offset the alternative minimum tax in the annual fix passed by Congress. They briefly raised the amount you could expense in a single year from $250,000 to $500,000. It is now back down to $139,000. All of these offers were short-lived, meaningless gestures.

Other so-called tax cuts are still in effect. The IRS no longer requires documentation for every cell phone call made or received to deduct the phone as a business expense. The penalty for tax errors at 75% of the mistake was capped. And they now allow $10,000 of startup costs to be deducted instead of just $5,000.

But all of these measures are insignificant. Businesses thrive or fail on their own in a free market. Government can stifle growth with taxes and regulations, but they can’t reward competitive businesses any better than getting out of the way.

Obama supports legislation to meddle more in the markets under the pretext of helping. He wants to increase 7(a) loans to small businesses that might otherwise not qualify because their loan applications are weak. The Community Reinvestment Act promoted people who shouldn’t borrow to buy a house, and now 7(a) loans fund businesses that shouldn’t borrow to compete with businesses that might be a much better bet financially.

These loans are also bad for lenders who must pay guaranteed fees of up to 3.5% of the SBA loan. The program is criticized as overly burdened with paperwork, taking too long to process an application or make good on a guarantee and poor customer service.

It reminds me of what Ronald Reagan called the nine most terrifying words: “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

The SBA uses formulas based on industry classification to define a small business. In my industry of portfolio management and investment advice, a small business is defined as revenue less than $7 million. Other industries use definitions based on the number of employees.

At stake is the definition of a small business. The SBA sets fewer than 500 employees as its threshold for research purposes. The Trump organization, cited by Obama in the debate, employs 22,000 people. Its annual receipts would far exceed any revenue limits. Any of its subsidiaries would fail to qualify for loans and other programs because they are not independently owned and operated.

Obama conceded that everything depends on if the top few percent he intends to burden are actually the job creators. Fortunately, the U.S. Census Bureau collects exactly that data.

Of the 29 million U.S. business establishments, 95.9% have fewer than 500 employees; 4.1% have 500 or more. The large businesses employ 50.6% of the workers; the small businesses employ 49.4%. Job growth, however, is not equal.

During the 2000s, large businesses grew leaner and more efficient as they consolidated and reduced employment. Small businesses, in contrast, grew into large businesses. If this were not the case, the percentage of large business employment would continue to grow indefinitely. As it is, large businesses lose employees but gain by graduating small businesses to maintain their half of the workers.

Small businesses create most of the jobs in America. But is this just the few percent that will be burdened as Romney suggests? It turns out it is.

The percentage of small businesses with 10 or fewer employees is 93.8%. In fact, 76.9% have no employees. Only 3.8% of small business establishments have 20 to 499 employees. But those businesses make up 64.0% of all small business employment.

Small businesses are essential to economic growth and employment. Disparaging their entrepreneurial growth as trickle-down economics misses the shower of prosperity.