How does Vanguard handle cost basis for mutual fund shares?

– Cost Basis Confused in Charlottesville

First a little background for those who have not had to deal with cost basis issues. Whenever you purchase shares of a mutual fund in a taxable account, the amount of money you put in is considered the cost basis for the shares you purchase. If you subsequently sell those shares for more of less than you paid for them you generate a capital gain or loss. You have to report capital gains on your tax return and pay capital gains tax each year. There are also complex rules for matching gains and losses and carrying forward capital losses to match against future gains.

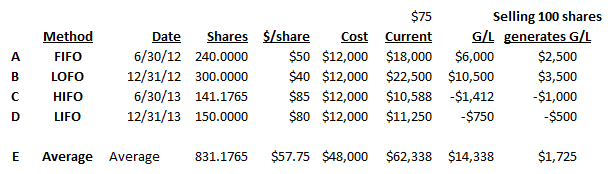

As an example, suppose that in the past you have made the following purchases of the same mutual fund, which is currently trading at $75/share:

Now suppose you need to make a withdrawal and you are selling 100 shares of the fund ($7,500). The shares being sold are from one of these purchases. How do you know which one?

The decision will have important tax consequences. Your gain/loss for each of the four trade lots varies from -$1,000 to +$3,500.

Custodians like Vanguard allow you to elect the default method of matching the shares you are selling to one of the trade lots in your account. Not every method is supported by every custodian. Here are the methods supported by Vanguard:

(E) Average Cost Accounting: This method can only be used for mutual funds. Stocks and exchange traded funds (ETFs) must use one of the other methods. This is the default at Vanguard, and is often a custodian’s default. This offers the least amount of tax planning. You are unable to pick the appropriate trade lot even if you wanted to generate a gain or loss. Unlike other methods, once this method is chosen, you can’t change it.

Because this is the default, and it not optimal, it is important for even novice investors to set a better trade lot.

(A) First In First Out (FIFO): Unfortunately this method is often selling one of the lowest cost trade lots and therefore generating one of the largest capital gains. This is probably the most tax inefficient method of matching trade lots.

(?) Spec ID: This option requires that every time you go to sell any of the mutual fund position you have to look up all of the trade lot identifiers and provide the custodian with the specific ID of the trade lot you would like to sell. This is certainly the most powerful. But you would still like a default methodology which you can use 95% of the time. So long as you have *not* chosen Average Cost Accounting, you can always use Spec ID on a specific sell order you are trying to do by writing specific instructions to the custodian asking them to sell a specific trade lot.

(C) Highest Cost (HIFO): This is *usually* the best for tax management. It selects the highest cost and therefore the smallest gain (or the greatest loss) for tax purposes.

Here are some additional methods which are *not* supported by Vanguard:

(D) Last In First Out (LIFO): This is often the best choice for tax management when a stock has been appreciating because the latest purchases will often have the highest cost. One of the problems with LIFO is that capital gains on holdings which have been held over a year are taxed at a lower rate than holding which have been held for less than a year.

(B) Lowest Cost (LOFO): The lowest costs is *usually* the worst choice for tax management. It will have the highest capital gain and therefore you will probably pay the most tax. There are two occasions where you want the lowest cost shares taken out of your account first. You may be in the 0% capital gains tax bracket and you are trying to generate capital gains up until the 0% capital gains tax treatment ends. Or you may be gifting shares to a charity and you want to give the shares with the lowest cost basis because the charity won’t have to pay any capital gains tax when they sell it.

(?) Tax Lot Optimized: The final method is fairly sophisticated. This is the method we default to at our custodian. It tries to do the wisest sale with reference to taxes that it can using the following methodology. Short Term Losses (D), Long Term Losses (C), Long Term Gains (A & B), and finally Short Term Gains (no examples). Within each of those categories it would sell using the Highest Cost First. Notice that this method would not sell the highest cost (C), but rather the highest cost short term loss. Short term losses can be taken against gains which might otherwise be taxed at ordinary income tax rates. This is usually better than taking a larger long term gain, but not always. The complexities of tax code make it dependent upon an individual’s specific 1040. For the times when you know a different method is better, a specific sale can always be put in against a specific trade lot (Spec ID).

At Vanguard, as well as most other custodians, the default trade matching methodology is *not* listed as one of the options on the initial account registration. Accounts that we open under our management default to “Tax Lot Optimized.” But accounts which are opened online through the retail side have their own default, usually Average Cost Accounting for mutual funds, and a different method, sometimes FIFO, for stocks and exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Therefore you must submit a second form in order to set your default trade matching methodology.

The form is called “Cost Basis Method Election Form” and is found here, or if that link become obsolete, you can do a search for “cost basis” amongst the Vanguard forms using this URL: https://investor.vanguard.com/search/?query=Cost%20Basis&category=ELFForms

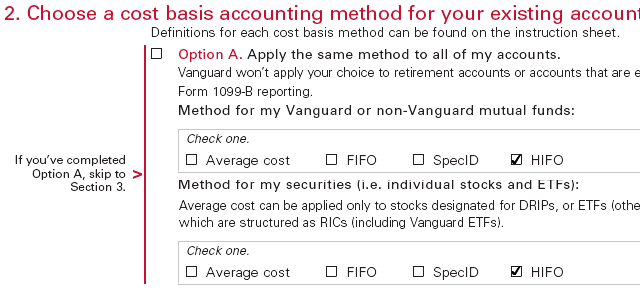

On the “Cost Basis Method Election Form” the best you can do at Vanguard is to select HIFO:

Finally, you should be aware of what constitutes a “Wash Sale.” A wash sale is when you sell a security at a loss, and then repurchase a substantially identical security within 30 days before or after the sale. In this case the IRS does not allow you to take the loss off on your taxes, and the cost basis of what you actually sold reflects your recent purchase of the substantially identical security.

If you have regular monthly purchases or reinvested dividends it is nearly impossible to avoid a wash sale. With purchases every month you will always have purchased some shares whenever you go to sell something.

For the casual investor I suggest you ignore the effects of wash sales. Vanguard (and other brokers) are not required to compute the tax consequences of a wash sale and adjust the cost basis of shares appropriately. If you are making $1,000 investments every month and then need to withdraw $30,000, and you have a trade lot with a significant loss, the wash sale rules will realize $29,000 of the loss and be subject to using the $1,000 trade lot that is within 30 days. For the casual investor, the benefits of saving and investing $1,000 every month or reinvesting dividends outweigh the potential wash sale if you you don’t think you are going to have frequent withdrawals.

But if you are making monthly withdrawals, it would be better to pay your dividends in cash and reduce your withdrawals by the average amount of the dividends in order to avoid purchases through the reinvestment of dividends to be immediately sold and potentially generate wash sales.

Since we are watching over a portfolio more frequently than the average investor, we usually pay all dividends and interest into cash and transfer monthly savings into an account in cash and then specifically purchase whatever components of the asset allocation which helps in the rebalancing of the overall portfolio. But if you are interested in setting your investments on autopilot, don’t worry about these wash sales.

Photo by Simon Cunningham used here under Flickr Creative Commons.