Investors are challenged these days to know where to put their money. Everyone wants to know which asset class will perform the best and help them meet their retirement goals.

Investors are challenged these days to know where to put their money. Everyone wants to know which asset class will perform the best and help them meet their retirement goals.

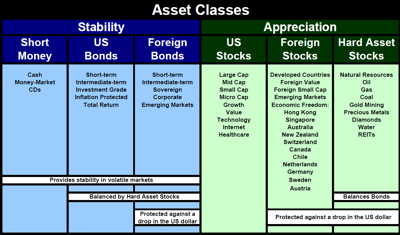

We use six different asset classes: three for stability and three for appreciation. In the stable asset classes, you loan a company money to be paid back at a fixed rate of interest. Examples include money market, certificates of deposit (CDs) and bonds. These asset classes are like the iron rods that support a sailing ship. They don’t make the ship go faster, but they do keep it from capsizing in a storm.

Investors approaching retirement should have at least five to seven years of their safe spending rate allocated to stability. For them, replenishing their allocation to stability when stocks are appreciating helps secure future years of spending.

In the appreciation asset classes, you own a piece of a company and share in its earnings. Examples include shares of individual companies or the mutual funds or exchange-traded funds that invest in equities.

Portfolio construction begins with the most basic allocation between investments that offer a greater chance of appreciation (stocks) and those that provide portfolio stability (bonds). These decisions are the most critical in determining the overall behavior of your portfolio returns.

We divide the asset classes for stability into short money, U.S. bonds and foreign bonds.

Short money includes any fixed-income investment with a maturity date of two years or less, which includes money market accounts and many CDs. Short money investments are not paying a great rate of interest right now. But when interest rates rise, they will adjust quickly and be among the first investments to gain from the higher rates.

Many risk-averse investors put their money in a bank account or invest in CDs. But like any other investment, cash has its own set of risks. It is dangerous because the dollar can be devalued so the same number of dollars won’t buy as much as they used to. There are good reasons to hold cash, but holding too much for too long makes it harder to grow your assets and can jeopardize your financial goals.

The second asset class, U.S. bonds, generally pays a higher interest rate the longer their duration and the worse their credit quality. But longer term bonds drop more in value when interest rates rise. And bonds whose credit rating drops lose value too because of the chance of default.

Putting money in stable instruments because you want to reduce risk only to invest in high-yield junk bonds is counterproductive. So is increasing the term of a bond when interest rates are very low. We recommend higher quality short- and intermediate-term bonds. Invest a portion of your assets in stable investments, and if you want a higher return, put the money into appreciating assets.

Foreign bonds are the third stable asset class. They can balance domestic currency values and interest rates with what’s happening in the rest of the world. And they sometimes pay a higher interest rate. Foreign bonds also appreciate when the U.S. dollar is declining in value. Foreign bonds are subdivided into bonds in developed countries and bonds in the emerging markets. Like U.S. bonds, foreign bonds are categorized by quality and duration.

Appreciating assets are essential to your portfolio. They are the engine of your retirement savings. Even in retirement, you will need enough appreciation to keep up with inflation, pay the taxes and still have some real return left over.

We divide appreciation into U.S. stocks, foreign stocks and hard asset stocks. Most investors have primarily U.S. large-cap stocks, mimicking the S&P 500. They buy mostly large-cap growth stocks in the industry that did well last year with a high price-per-earnings (P/E) ratio. We don’t recommend such portfolios.

On average, small cap outperforms large, and value outperforms growth. Although we recommend overweighting smaller companies with low P/E ratios, your portfolio should include a broad spectrum of stocks, including a generous helping of growth-oriented stocks. There may be times to overweight or underweight specific industries such as technology or health care.

The second appreciation asset class is foreign stocks. Diversification abroad can both boost returns and decrease volatility. Some people try to diversify internationally by investing in U.S. companies that gain a significant portion of their revenue from overseas. But these multinational companies still track fairly closely with other domestic companies, and they don’t offer the same benefits as investing in foreign stocks.

Overweighting specific countries can be advantageous too. We use the Heritage Foundation’s ratings to select countries that combine the greatest economic freedom with large investable markets. One yardstick of economic freedom favors countries with a low public debt and deficit and therefore a more stable monetary policy.

We recommend investing in the fastest growing countries. These emerging economies provide even greater diversification and returns. However, emerging markets are inherently volatile, so it is important to find the right balance and make adjustments as needed.

Finally, hard asset investments include companies that own and produce an underlying natural resource. These include oil, natural gas, precious and base metals, and resources like real estate, diamonds, coal, lumber and even water. We suggest diversifying hard asset stocks by resource type, geographic location of a company’s reserves and company size.

Investing in hard asset stocks is not the same as investing directly in commodities. Buying gold bullion or a gold futures contract is an investment in raw commodities or their volatility. But buying a gold mining company is a hard asset stock investment.

Over time, dollars lose their buying power, and the goods and services we buy cost more. Commodities generally maintain their buying power in dollar terms. But investing in hard asset stocks generally appreciates at a rate much higher than inflation.

Hard asset stocks have a distinct set of characteristics and are categorized separately. Their movement is generally less correlated with that of other asset classes. They have a unique (and positive) reaction to inflationary pressures. And at certain periods in the longer term economic cycle, including hard assets helps boost returns.

Many advisors don’t have an asset class for natural resource stocks. They select one portion of the category instead, typically real estate, and make that the asset class. This can be a good idea. Real estate indexes have correlations as low as 0.49 against the S&P 500. We use real estate as a subclass within the natural resources category because at times it has a low correlation with energy and other commodity movements.

Natural resource stocks have an even lower correlation to U.S. bonds. Natural resources (commodities) often exhibit a negative correlation to fixed-income investments due to their inverse relationship to inflation. So their optimum allocation depends on both the amount designated to stocks and the amount designated to bonds.

Many U.S. investors crowd their assets into a combination of large-cap U.S. stocks and U.S. bonds. This allocation represents only one and a half of the six asset classes described here.

Asset allocation means always having something to complain about. Investors are continually looking for the safe investment. But inflation, sovereign debt, globalization and diminishing U.S. economic freedom make a clear choice difficult. Thus we advise a diversified portfolio that overweights certain subcategories.

If you have set such an asset allocation, what did poorly this past quarter may be poised to do better in the coming year. If your asset allocation is wrong, change it. But if it is right, don’t abandon a brilliant allocation simply because of short-term returns.

Finally, rebalance regularly. Without rebalancing, those categories that do well may continue to grow as a percentage of your portfolio until they significantly underperform the markets. The ones that do the best often bubble and finally burst.