Originally Written September 6, 2002

World War II was unlike any other war in which the United States engaged. I was just a young squirt, but I cannot think of another time in my life when I thought that our country was so closely united. There was no great divide between those who were in the military services and those who remained at home. With only a few exceptions, every single person was a part of the war effort and felt that they were contributing. Everybody had a part to play and that contributed greatly to speeding the outcome of victory.

For example, in our family of five brothers, three of us were in the military. One was too young to participate and one was in a vital industry (railroading) and was not called up because of that.

Everyone remembers where he or she was when the news of the Japanese attack came in. The bombs were still falling when the news reached most Americans via radio. Millions were listening to the Columbia Broadcasting System that afternoon when, just as the New York Philharmonic was tuning up for Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 1, John Daly’s familiar voice broke in a few minutes after 3 p.m.: “We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin. The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor.”

In the 16 days that followed Pearl Harbor, railroads on the home front moved more than 600,000 troops. Train stations and bus terminals became kaleidoscopes of olive drab, navy blue and marine green. The uniforms, like many other things in military life, were known as Government Issue, or GI. And the swarms of men who wore them took for themselves the same unromantic label, GI. Though many GIs were volunteers, fully two thirds joined up through a system that was largely alien to America: conscription. Until 1940, the U.S. had been one of the few countries in the world that lacked a program of compulsory military training. In September, Congress approved the first peacetime draft in American history.

The new law required all men between the ages of 21 and 35 to register with their local draft boards on the 16th of October 1940. On that day, at 6,175 draft boards across the country, 16,316,908 men registered. Every man who registered received a number. Two weeks later, President Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson met around an enormous glass bowl to determine the order in which the registrants would be drafted. The bowl, which had been used for the same purpose in 1917 when the U.S. entered World War I, contained 9,000 bright blue capsules. In each capsule was a numbered slip of paper. The first number picked was 158. Across the land there were 6,175 registrants with that same number.

Most Americans who were physically and mentally qualified were ready to take up arms for their country, but a small percentage chose not to serve for reasons of conscience. Of the over 10 million who were ordered to report for induction, only 43,000 objected by reason of religious training and belief. And 25,000 agreed to serve as medics or other lines not requiring them to bear arms. Another 12,000 worked at alternative nonmilitary service in 151 Public Service Camps. The remaining 6,000 refused to serve in any capacity and were sent to prison.

Uncle Sam was not too fussy! They were so desperate for manpower, that special draft boards were set up in most state and federal prisons, and more than 100,000 convicted felons were taken into the armed forces. There were dozens of classifications from 1-A to 4-F (physically, mentally or morally unfit for service). Those who were classified 1-A soon found a form letter in their mailboxes. “Greeting,” it began “…you have been selected for training and service in the Army.” A member of the local draft board signed it. Usually only the Army drafted men, as the other services had the benefit of volunteers. If you had flat feet, you were supposed to be 4-F, but they merely felt my arm, which was warm, and drafted me into the Army Infantry anyway.

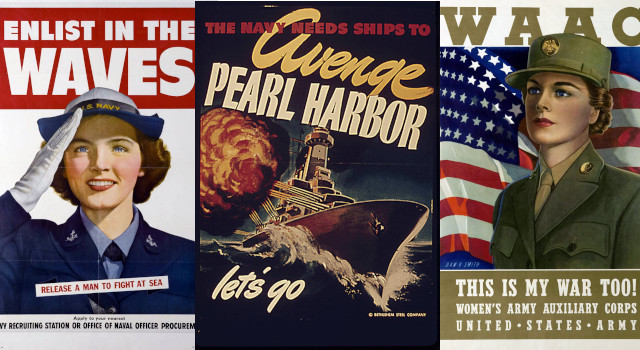

There was such a shortage of manpower that the military services recruited some 200,000 women. They served in the WAACs (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps). Then the Navy took some 77,000 into the Women’s Naval Reserve. They were called WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). The Army Air Forces had WAFs women pilots to ferry planes from factories to air bases. WWII was great for these shorthand acronyms.

Coming from an Italian family, we were a little embarrassed that Italy had declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941. But we, of course, were loyal to the United States. I am sure that was the feeling held by families of German and Japanese descent also.

But the Japanese-Americans were not as lucky. In 1941, there were 127,000 persons of Japanese ancestry in the US. Some 80,000 were native-born American citizens, or Nisei. Most of the Nisei were truck farmers in California. They were suspected of sabotage, and public pressure caused the politicians to act. In February 1942, President Roosevelt ordered the War Department to move the Nisei out of California. They were rounded up, forced to sell their property. They were moved out to the Western desert. They were forced to harvest crops by day; and were kept in barbed-wire compounds at night. Fifty-two years later, in 1994, Congress condemned the relocation policy as a product of “war hysteria, racial prejudice, and failure of political leadership.” They compensated internees with a payment of $20,000 each.

Also while the nation fought against the world’s worst racist, it maintained a segregated army abroad and a total system of discrimination at home. In the nation’s capital, African-Americans got their water from separate drinking fountains, used segregated toilet facilities, could not eat in “white” restaurants, sat in the balcony in their own section in movie theaters, and sat in the back of the bus. Throughout the South, and in much of the North, blacks could not vote. In May 1941, President Roosevelt issued an Executive Order forbidding racial discrimination in defense industries and established the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

In the summer of 1943 there were race riots in several cities as Blacks protested their segregated treatment. In 1944, the Army ordered the desegregation of its training camp facilities. It was not until after the war — July 26, 1948 — that President Truman signed the order officially desegregating the armed forces. Despite everything, however, many African-Americans did improve their financial situation, most of them by moving out of the rural South to the urban North and West and taking jobs in war industries. Also the process of integration of the armed services got its first start during the war.

Right after Pearl Harbor, there were many communities in America that suffered from the war jitters. The top officer of the American Legion in Wisconsin appealed for the creation of a guerrilla army that would be composed of the state’s 25,000 licensed deer hunters —”a formidable foe for any attackers,” he insisted. In early 1942, the West Coast feared attacks from Japanese submarines.

For the United States, 300,000 Americans were killed in combat out of an armed force of some 16 million. Compared with that of most other combatants, this death rate was extremely low. Those who suffered most were the Jews, Soviets, Germans, Japanese, Poles, Yugoslavs, Filipinos, and Chinese.

Although there was some destruction of property in Hawaii, a great deal in the Philippines, and on Sitka and Attu, there was none in the forty-eight states. Americans at home were insulated from the direct effects of war. The biggest difference between America in the 1930s and the first half of the 1940s was that everyone had a job. Unemployment fell from 25 percent to 1 percent, and that 1 percent consisted of people moving from one job to another.

Between 1939 and 1945 per capita income doubled, rising from $1,231 to $2,390. Thanks to wage and price controls, inflation was moderate.1 Since there were no new cars, new homes, washing machines, or other durable consumer goods for sale, most of the income went into savings. Savings went from $2.6 billion in 1939 to $29.6 billion in five years, a tenfold increase.

Most Americans in 1940 had never been out of their home state, many of them never out of their local county. Only a tiny percentage had ever been overseas. Between 1941 and 1945, some 12 million young Americans went overseas into a different culture and part of the world. Within the US, more than 15 million civilians moved during the war, over half of them to new states. This mass migration dwarfed the westward movement of the nineteenth century. This mass migration helped break down regional prejudices and provincialism. For most of them the magnet was jobs. California shipyards and aircraft plants alone attracted 1.4 million people, helping to set the stage for the state’s later ascendancy as the largest population center in the United States.

No other area of the country felt the effects of the migration more sharply than the South. Scores of military camps were located there. For example, Starke, Florida, once a depressed town of 1,500, overnight became the state’s fourth largest city when Camp Blanding, a post for 60,000 soldiers was built nearby. A lot of shipbuilding took place on the Gulf Coast. In Mobile, Alabama, the population shot up 60 percent in three years. So crowded was the area that landlords rented so called “hot beds” to workers in shifts—eight hours rest for 25 cents.

The lack of housing was critical around the Ford aircraft plant at Willow Run, Michigan. The plant attracted 32,000 workers and the spic and span nature of the factory floor contrasted sharply with nearby living conditions. In one house, there were five men living in the basement, a family of five on the first floor, four people on the second floor, nine men in the garage, and four families in four trailers parked in the yard.

Remember during WWII, there were no shopping centers, no malls, few drive-ins or suburbs, almost no air-conditioning. City dwellers went to shop “downtown” in solid masonry buildings of two or three stories. There were almost no four-lane roads. Almost every family in 1945 had a radio; there were 34 million households and 33 million had a radio — and that by the way was more than had indoor plumbing!

Cigarettes were scarce, and many people learned to roll their own. The ration stamp was a necessity of life for meats, butter, sugar, and coffee, almost all canned and frozen foods, gasoline, and shoes. There were tin can collections, wastepaper collections, and aluminum drives; housewives even salvaged grease from cooking.

Automakers were ordered to stop building family cars in 1942; gas was rationed, and tires — even retreads — were in short supply. Gone from store windows were new toasters and refrigerators, irons and washing machines — in fact most household appliances. Meat eaters got by on 28 ounces a week. Butter lovers were held to an average of 12 pounds a year. Coffee drinkers made do on a pound every five weeks. Sugar ration was 12 ounces a week. Cigarettes were hard to come by, because 30 percent of production went to the military. There were shortages of some 20 items that went under the rationing system. Housing was particularly scarce.

There is a story about a man drowning in the Potomac River in Washington, D. C. whose cries for help attracted a passerby. “What is your name and where do you live?’ demanded the passerby. “John Jones, 14 North S Street — Help!” the drowning man gasped frantically. The passerby immediately rushed to that address and breathlessly told the landlady, “I want to rent John Jones’s room. He just drowned.” “Sorry,” replied the landlady, “it was just taken by the man who pushed him in.”

For entertainment other than the radio, people went to the movies. In 1945, some 85 million went to the movies each week. Almost everyone saw the popular movies, such as Casablanca, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, Bambi, and Guadalcanal Diary.

During World War II, more than 425,000 Axis prisoners of war were held in the U.S. At the war’s end, some fought deportation to homelands ravaged by war and stayed in America.

For young women, the war brought great change. There were no young men around, so women spent more time with each other. Housing shortages, especially around military bases, forced young women to share living space, frequently five or more to one home, with one bathroom and one kitchen.

Gasoline was rationed — three gallons per week — but not to save gas, which was abundant. Rather, it was to save rubber, which was impossible to get after Japan overran Southeast Asia. The national speed limit was 35 mph (also to save rubber).

Women entered the workforce in record numbers. “Rosie the Riveter” was a common expression. About 3 million women worked in war-related industries. Young mothers managed to balance night shifts with childcare. Quickie marriages were the norm. There were a million more marriages during the war than would have been expected at prewar rates. Teenagers got married because the boy was going off to war. In the moral atmosphere of those days, if the couple wanted to have sexual relations before he left, they had to stand in front of a preacher first.

Although the year 1946 was the peak year for divorces, most marriages did work.

More than three million women joined the Red Cross to run canteens or serve as nurse’s aides or drive ambulances. More than one million others provided food, entertainment, company and good cheer for lonely servicemen at USO centers across the nation.

Most wives and girlfriends were faithful to their men, but occasionally there would be lapses. For GIs the greatest joy came from receiving letters from their loved ones at home. However, the most dreaded letter was from a girlfriend that began with “Dear John” informing him that she had taken up with another man.

Many GIs came home to find that their wives had become much more independent. The new self-sufficiency stemmed from the fact that more than six million women, half of them married, had experienced for the first time the excitement and independence of earning their own paychecks. For them divorce, or the prospect of living alone, lost some of its terror.

During the six-year war, no elections were held in Europe, Asia, Africa, or the Middle East; even in Great Britain elections were suspended for the duration. But the United States during those six years saw two presidential, three congressional, and hundreds of state election, all hotly contested.

People were encouraged to grow gardens to raise food that was scarce. They were soon named Victory Gardens. It was something the whole family at home could do to feel like they were contributing.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, labor leaders took a no-strike pledge. Strikes cost less than half of 1 percent of all work time. The most notorious strike in 1943 was held by about 400,000 coal miners who demanded higher wages. Their leader was John L. Lewis. The strike was long and caused some shortages along the East Coast. Lewis was for a time the most unpopular man in America.

Many returning servicemen did not want to talk much about what they did during the war, especially those who were in combat. It wasn’t until Tom Brokaw published his book on “The Greatest Generation,” that families began to open up and talk about their activities and feelings during WWII.

The worst thing that could happen to an American family during the war was to receive a telegram from the War Department informing them that their son was killed in action. Among the thousands of servicemen killed on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was a sailor by the name of William Ball, from Fredericksburg, Iowa. When Ball’s boyhood buddies, the five Sullivan brothers from the nearby town of Waterloo, received word of his death, they marched out together to enlist in the Navy. The Sullivans, who wished to avenge their friend, insisted that they remain together, and the Navy granted their wish. On November 14, 1942, the cruiser the brothers were serving on, the U.S.S. Juneau, was hit and sunk in a battle off Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. Two months later, Mrs. Sullivan received the news, not by the usual telegram, but by a special envoy. The family became a national symbol of heroic sacrifice, further enhanced by the fact that the only remaining child, a girl, enlisted in the Navy as a WAVE.

The war had an enormous cost — more than $330 billion in military expenditures over a four-year period. Tax programs and War Bond campaigns helped to finance the effort. The federal government imposed a 5 percent surcharge on all income taxes — a Victory Tax. Then Uncle Sam began requiring employers to deduct from workers’ paychecks the appropriate percentage of wages due as income taxes, which hitherto had been paid once a year.

This was the beginning of the withholding tax that, to this day, diminishes the paycheck of every American wage earner.

The Treasury’s other major source of immediate cash was War Bonds, which could be bought in denominations ranging from $25 to $10,000. Americans purchased some $135 billion in bonds during the War.

World War II was a period of explosive growth for the U.S. The population reached 140 million during the war, up nearly eight million from 1940. The federal budget soared to $98 billion, more that 10 times the $9 billion budget of 1939. The GNP leapt to $213 billion, up from $90 billion in 1939. The total labor force grew to an all-time high of 66 million. College and university enrollment was climbing toward 1.7 million from a prewar high of 1.4 million. Federal government employees increased from one million to 3.8 million.

Teenagers found new independence as they entered the workforce. Young female bobbysoxers swooned over the scrawny young man from Hoboken who was classified 4-F because of a broken eardrum — Frank Sinatra. Also, male teenagers showed their independence through their crazy dress of zoot suits — long jackets and pleated trousers. The zoot suit, which originated among teenagers in Harlem and other urban slums, became a widespread fad. A song helped enhance its popularity: “I wanna zoot suit with a reat pleat/With a drape shape and a stuff cuff.”

Military photographers were often assigned to factories to take pictures of the all-American girl working in a factory. These were shown to the men in combat for moral purposes. It was on such a mission that an Army photographer discovered a curvaceous 19-year old beauty at the Radio Plane Parts Company in Burbank, California. She was spraying the fuselage of a plane and radiating sex appeal. Her name was Norma Jean Baker, and she agreed to pose only after the photographer had secured written permission from her foreman. After her pictures appeared in Yank magazine, another photographer took pictures that he gave to a modeling agency and the rest is history for Marilyn Monroe.

As Edward R. Morrow would say at the close of his popular news broadcasts, “And that is the way it was on the home front during World War II.”

1) There was 10.3% inflation six months before the controls, 3.5% during controls (4/42 – 6/46), and 28.0% six months after controls. You can read more in “Price and Wage Controls in Four Wartime Periods” by Hugh Rockoff or “Prices, Income, and Monetary Changes in Three Wartime Periods” by Milton Friedman.

Photo of WAVES poster, Navy poster, and WAAC poster used here under Flickr Creative Commons.