In your article “Bond Investing In 2016” you described a bond laddering strategy using bond exchange-traded funds. If one were to employ that strategy for IRA required minimum distributions (RMDs), six years would be an allocation of approximately 25% (6 yrs times 4%) in bonds or cash and 75% in stocks.

What is the best way to empty and refill those buckets once I start taking RMDs? In other words, if bonds outperform, does one “dip into” the six-year bond bucket and buy stocks in order to maintain the 75/25 allocation?

Also, if there is no outperformance, I suppose one would spend the bonds down in the order you listed, refill the bond buckets as you withdraw from the cash bucket, and finally refill the Emerging Market bond bucket by selling equities and buying VWOB. Does this sound reasonable?

Yes. When you use a bond laddering strategy with funds, rebalancing to your asset allocation naturally buys and sells bond funds as appropriate.

If you are creating a laddered bond strategy using individual bonds, an investor would periodically purchase 6- or 7-year bonds which would mature in the year in which the money was needed to be spent or distributed.

A bond laddering strategy using exchange-traded funds is both much more flexible as well as much simpler to implement.

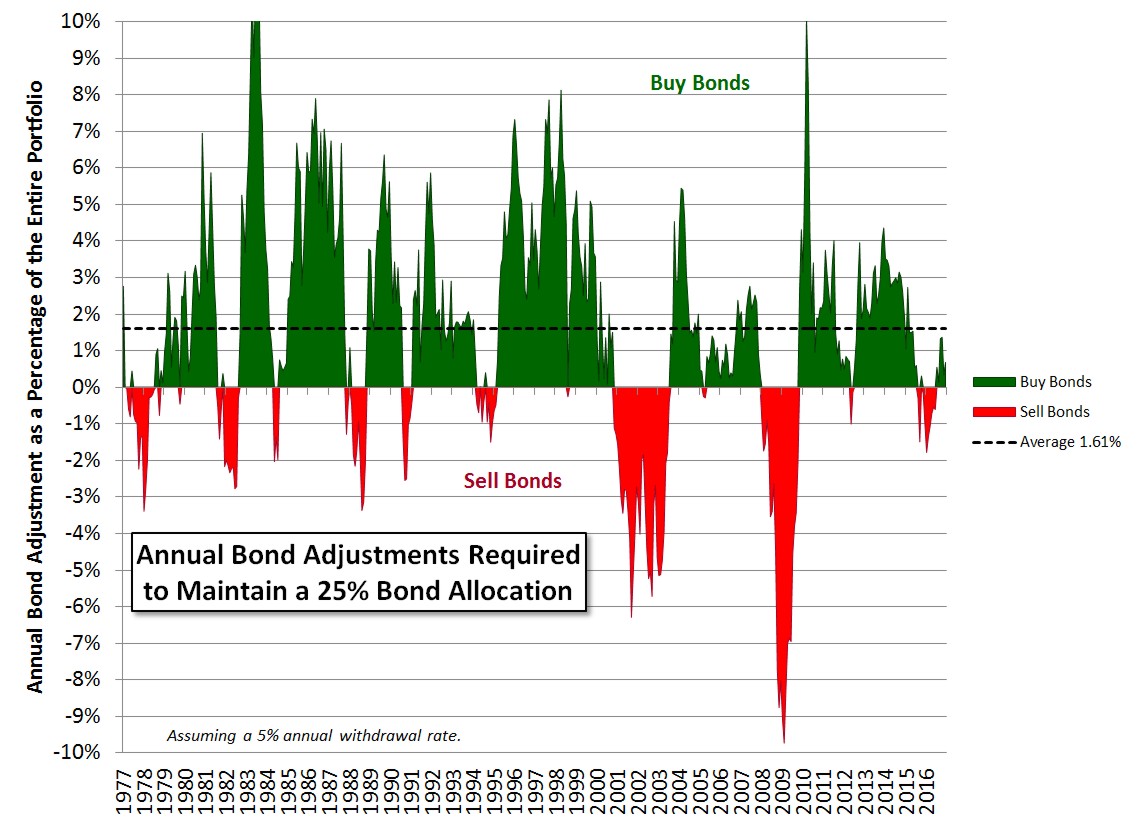

I ran a 41-year historical simulation using 1976 through 2016 of an account which was allocated as 25% in the Bloomberg Barclay’s US Aggregate Bond Total Return Index and 75% in the S&P 500 Composite Total Return Index. I burdened the account with a 5% annual withdrawal rate, and rebalanced it back to this asset allocation monthly. Then, I measured the amount of bonds I needed to buy or sell over a rolling 12-month time period.

During this time period, stocks, as represented by the S&P 500 Composite Total Return Index, had an annualized return of 11.37% and bonds, as represented by the Bloomberg Barclay’s US Aggregate Bond Total Return Index had an annualized return of 7.55%. The blended portfolio had an annualized return of 10.63%.

Because the portfolio appreciation (10.63%) was greater than the withdrawal rate (5.00%) on average, the portfolio’s total value grew. In order to maintain the constant 75% stock and 25% bond allocation, bonds had to be purchased each year, averaging 1.61% of the total portfolio value. Meanwhile, stocks needed to be trimmed by about 5.02% of the total portfolio value each year in order to keep them from exceeding the 75% allocation.

While the average year involved purchasing bonds, anytime the stock market dropped precipitously rebalancing entailed selling some of the bonds in order purchase stocks and meet withdrawal needs. This is why the bonds are there: to ensure a few bad years don’t make you run out of money.

Here is a chart showing the annual bond adjustments required to maintain a 25% bond allocation using the rolling 12-month amount of bonds which need to be bought or sold as a percentage of the entire portfolio. For example, during the 2000 to 2002 time period, you would have had to sell an amount of bonds worth about 4% of the entire portfolio in order to rebalance the portfolio. Because of the drop in the portfolio value, the bond allocation might have grown from 25% bonds to 29% bonds. Selling bonds worth 4% of the entire portfolio might have been necessary in order restore the balance.

A bond allocation not only provides cash for spending withdrawals during precipitous markets, but it also provides cash for rebalancing into the markets after they have fallen.

When you withdraw cash and need to replenish it, rebalancing will simply sell whatever is appropriate. If you have bond funds which represent different time periods, money does not need to flow between the different time periods in order to maintain the laddering strategy. You may, if stocks have appreciated, simply sell some stocks to generate cash and keep your bond fund allocation the same. This is equivalent to the below alternative process which would be necessary if you invested in individual bonds instead of bond funds:

- Selling some short-term bonds to replenish the cash.

- Selling some aggregate bonds to replenish the short-term bonds.

- Selling some inflation-protected bonds to replenish the aggregate bonds.

- Selling some international bonds to replenish the inflation-protected bonds.

- Selling some emerging market bonds to replenish the international bonds.

- Selling some stocks to replenish the emerging market bonds.

Obviously if stocks have appreciated, it is much simpler to simply sell some stocks to generate cash. And if stocks have dropped precipitously you would probably have to trim each of the bond positions in order to maintain the correct asset allocation. Or in in the short-term you could simply liquidate the short-term bonds to generate cash for withdrawals and stock purchases. Then if stocks recover quickly you can sell some of the appreciated stock and replenish the short-term bond allocation.

Any portfolio which is subject to regular withdrawals should have 5 to 7 years of withdrawals in a stable bond allocation. Such an asset allocation may provide you with the best chance of supporting those withdrawals. Having everything in stocks risks having to take money out after poor market returns early in the sequence and therefore not having enough money remaining to grow when the markets recover. A portfolio which includes some bonds and is regularly rebalanced can provide you with a better chance of meeting the goal of your withdrawals.

Photo used here under Unsplash Creative Commons Zero.