Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are a cost-effective way to build a well-diversified portfolio, but don’t just assume that all are inexpensive and diversified. Warren Buffet has been known to warn novice investors with a poker analogy. Buffett shares that if you don’t know who the patsy is after 30 minutes of playing, you’re the patsy. Those who fail to do their homework will pay the price.

ETF market share has doubled in the last five years during the same period that mutual fund market share has been relatively stagnant. Although ETFs are generally cheaper and more tax-efficient than mutual funds, it’s important to count all the costs. Some newer ETFs, such as leveraged funds, appear to do a better job at maximizing fees than providing a healthy return to investors.

You cannot control the ups and downs of the market, but you can keep costs to a minimum. Some expenses are easy to comparison shop. You can find any ETF’s expense ratios and commission prices easily on brokerage or fund websites. But another cost, the bid/ask spread, is not readily disclosed and will require some additional digging to determine.

Expense ratios

The largest portion of your ETF costs is the expense ratio, the internal fee the fund company charges. This fee is extracted daily over the course of the year. ETF expense ratios are usually lower than mutual funds, largely because ETFs don’t need as many people to run them.

When you purchase an ETF, it requires little more administration than buying an individual stock. Mutual funds are different story, though. Mutual funds require recordkeeping operations and call centers. This extra administrative burden explains why ETFs can offer their product with a lower expense ratio.

But don’t assume the lower costs of lighter administration will be automatically passed along to investors. Some ETFs see this reduced cost as an opportunity to maximize their profits.

There is no good reason to pay more than 1% for any investment fund. Even this threshold may be too high, but it’s easy to remember. You can find the expense ratio listed on most financial websites or in the fund’s fact sheet and prospectus.

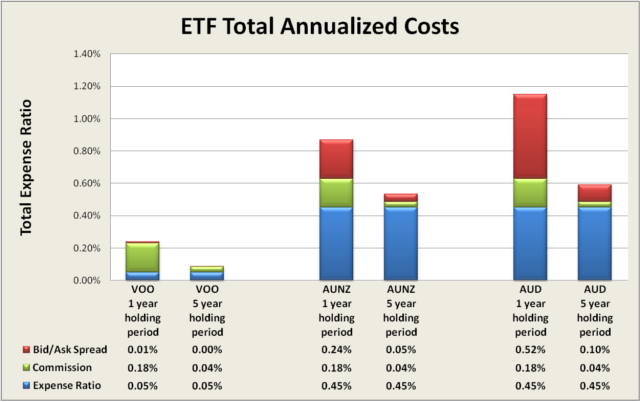

In the chart below, you can see that the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO) has a minimal expense ratio of 0.05%. On a $10,000 investment, the annual expense ratio cost of holding this ETF is $5. Expense ratios climb as you seek out funds that target more obscure markets.

Our investment committee recently searched for a fund that gives us exposure to Australian bonds denominated in local Aussie dollar currency. Two similar ETFs that offer this are the WisdomTree Australia & NZ Debt ETF (AUNZ) and the PIMCO Australia Bond Index ETF (AUD). They both have the same expense ratio of 0.45%, but if you look beyond expense ratios, the carry very different costs.

Commissions

Your broker charges a commission on most investments bought and sold on an exchange. Commissions fell dramatically over the years as trading moved online and away from floor traders. Back in 2000, an equity purchase from Charles Schwab typically charged $29.95. Today, the same purchase only costs $8.95.

Trading ETFs frequently is a surefire way to make your broker rich. If you buy 1,000 shares of any ETF every month for a year, you pay 12 separate commission. That can mount up.

Commissions shouldn’t worry a long-term investor. For a $10,000 position, buying and selling the same position within a year will costs you $17.90 ($8.95 × 2) or 0.18% annualized. If you hold this position for five years before selling, the expense of commissions is just 0.04% annualized.

Bid/Ask Spreads

The third expense to consider is most often overlooked, but can be the most significant cost if you are not careful. In the day of floor traders, bid/ask spreads were determined through a cacophony of voices yelling their buy and sell offers. The difference between the lowest sell offer and the highest buy offer is called the spread. Today, limit orders (programs that stop buying or selling after a security reaches a certain price) or market makers who publicize their best offers set the spread.

If you can buy an ETF for $10 per share or at the same time sell the same ETF for $9.95 a share, the spread is 5 cents, a cost of 0.5%. Like commissions, bid/ask spreads are transactional charges. The more often you trade, the more you pay.

The bid/ask spread is most costly in thinly traded positions. The VOO ETF has trading volumes of nearly a million shares every day, and the spread is an inconsequential 0.01%. However, fewer than 8,000 AUD shares exchange hands every day, and the average spread is 0.52%. That’s a 52 times greater cost due to poor liquidity.

Even if held for five years, the bid/ask spread adds a significant 0.1% annualized cost to a $10,000 investment in AUD but only half this cost for a similar investment in AUNZ. Our investment policy committee decided to go with AUNZ to minimize these costs.

Researching bid/ask spreads offers several challenges because most companies do not clearly communicate this cost. Morningstar offers this spread in their summary statistics but the spreads are reported in real-time which means they are constantly changing. When I was researching the bid/ask for AUD, it changed from 0.07% to 1.2% within a few hours.

Checking these spreads after trading hours is not a good gauge either. At the end of the trading day at 4:00 p.m. Eastern time, market makers often remove their bid and ask prices for ETFs. That’s to avoid getting caught in an unprofitable trade first thing in the morning if the index moves overnight. This causes the bid and ask prices to move away from one another and the spread to balloon.

There is a good way to determine the spread and account for volatility. If your ETF trades less than 100,000 shares per day, call the fund company and request the closing bid/ask spread for the last month. By taking an average of these spreads, you can fairly gauge what the typical cost might be. Additionally, if you are planning to purchase a larger amount of shares than is typical, I recommend you use a limit order to protects your purchase price.

Before purchasing an ETF, study the expense ratio, your commission price, and the bid/ask spread. That way you’ll know you’re not the patsy.

2 Responses

Dale Seng

Nice to know that info Matt. I’m the patsy when it comes to ETF’s, but I only buy stuff you, David, George, or one of you guys recommend, so that helps. And I don’t know if I’m being “overly cautious”, but I’ve used limit orders so far; I don’t mind paying the median of the day, I just don’t want to be the dude who paid the most, hehe. At times, my order hasn’t been filled, but I got my order filled in the next few days. Luckily, I’ve never had to “chase it” higher, but I was worried about that once. In that case, you’d be penny wise, pound foolish (in hind sight).

This might be a question for another day, but I wondered about the benefits of an ETF that’s “denominated in (some non-USD) currency”. I’ve taken to heart a bunch of the overseas gone fishin’ stuff, but those all trade in USD, while the underlying ownership is in other countries. If it’s a tax reporting edge, I have a feeling that since most of what I have is in Roth or IRA, it might not make much difference to me. But I’d be interested in why this matters to you and your clients.

Matthew Illian

Dale, I was not meaning to imply that we hold foreign currency accounts but to simply distinguish between a fund that is hedged against currency movements. All of the funds that we buy and sell are with USD$. When buying a fund (with USD) that holds assets denominated in a non-USD currency, this means that daily currency movements will impact the price of that fund – in additional to the underlying fundaments. Some funds chose to buy futures contracts to hedge these currency movements. We avoid these hedged funds because they carry an extra cost to purchase the insurance.

We also prefer the currency movements because as long as we are holding healthy currencies, this gives us an opportunity to rebalance over time. For 2012, the emerging markets stocks (as measured by MSCI) was us 13.94% but when measured in USD (which depreciated relative to emerging market currency), it was up 15.15%. http://www.msci.com/products/indices/country_and_regional/dm/performance.html.