Many people do not know that the required minimum distribution (RMD) divisor table is based on life expectancy. At age 71, they estimate you could live 26.5 years longer, to the age of 97.5. That is why they make you take out 1/26.5th share of your account. In their mind, this is one year’s worth of your IRA.

However, the IRS also has favorable marriage rules when it comes to retirement accounts. Whereas anyone else inheriting your retirement account would need to open an Inherited IRA and begin taking harsher inherited RMDs, your spouse is allowed to do a Spousal Transfer and treat the IRA as his or her own for the purpose of calculating RMDs.

This rule was created to protect a working husband’s stay-at-home wife from having to take massive inherited RMDs on her husband’s 401(k) before she is actually of RMD age. Instead, the 401(k) or IRA is considered to be their retirement savings, not just his.

These two factors – divisors based on life expectancy and retirement accounts being viewed as both couple’s money – created an issue for couples with a wide age gap. If a 80-year-old and a 20-year-old were married, the younger spouse might not get to inherit much of the retirement account because the older spouse’s RMD would be high (18.7 or 5.35% of the account) and growing annually.

For this reason, the IRS made a Joint divisor table. They arbitrarily decided that a difference of more than 10 years in age is sufficient to warrant an entire new set of divisors just for mixed-decade marriages.

The Joint divisor requires that your younger spouse be your sole primary beneficiary to qualify since the idea is based on it being their money one day, but assuming you meet this and the age requirement, you can use the lower Joint divisor.

For our example 20-year-old and 80-year-old, this is the difference between 18.7 (the Uniform divisor) and 63.1 (the Joint divisor). In that case, the Joint divisor lets 3.76% more of the IRA stay in the account.

At first glance, this may seem like a small benefit at first glance, but it has large effects over time.

Imagine a couple with 11 years of age difference with a Traditional IRA worth $1 million when its owner, the elder, turns 70. Imagine, for simplicity, they are always in the 25% federal income tax bracket and the 15% capital gains bracket. They will take RMDs for 23 years and reinvest the RMDs in their brokerage account. Those investments, whether or not they would have stayed in the IRA or end up in the brokerage account, receive an annualized return of 10%. When they use the Joint divisor, the IRA retains a greater percentage of their net worth and they pay less income tax because of their smaller RMD.

The IRS makes sure you can’t keep assets in your IRA forever. Eventually, all Traditional IRA assets will be distributed and the government’s portion will be taken. Because of this, it is unfair to simply compare the effect of the divisor used on this couple’s net worth. More funds left in the IRA are more funds still unburdened by federal taxation, leading to a higher net worth in the short-term, but not the long-term when the money will certainly be distributed and taxed.

Instead, we need to compare the couple’s after-tax net worth. In both cases, their $1 million IRA has an after-tax value of $750,000 because 25% (their marginal rate) will be lost to taxes over the course of their withdrawals. If this were the only relevant tax, the Joint and Uniform divisors would have no difference in the end. Capital gains taxes that act on the growth of money in the brokerage account make the difference. A more aggressive rate of withdrawal puts more money in the brokerage account where the growth will be taxed. A slower rate of withdrawal, which the Joint divisor allows, means less money will be subject to capital gains taxes over the long-term.

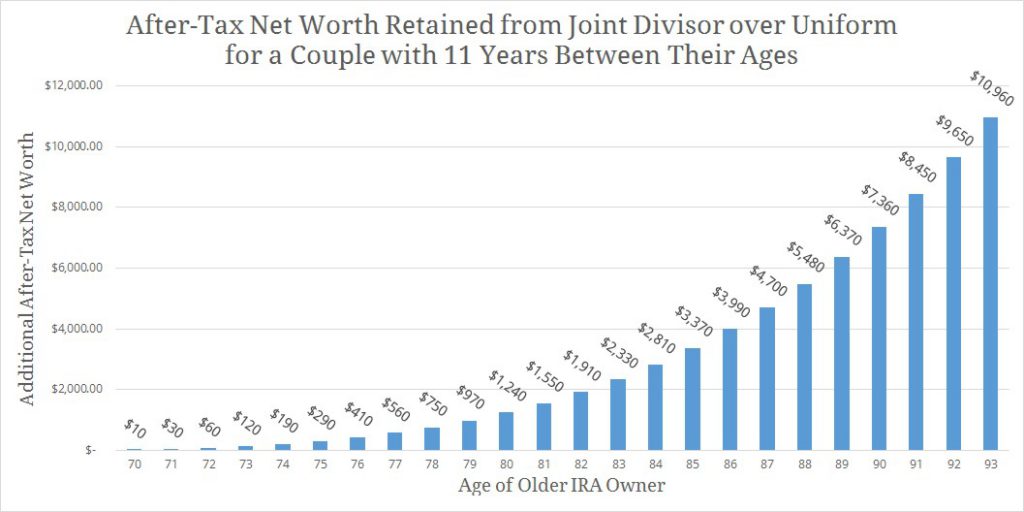

To calculate our hypothetical couple’s after-tax net worth, their IRA assets are reduced by 25% and their brokerage account by 15% of the gains. This graph then shows the difference in their after-tax net worth between the Joint and Uniform divisors for ages 70 to 93.

By age 93, the Joint divisor is worth over $10,000 in after-tax net worth, 1.10% of their initial investment.

If this couple used their RMD to justify increasing their spending budget and did not save any of it, the after-tax value of the Joint divisor over the Uniform would be over $96,000. The temptation to spend RMD money simply because it is available is natural, but dangerous.

The benefit of the Joint divisor is even greater if the heirs of the account (even the spouse) are, or will be, in a lower tax bracket than the current owner. A smaller RMD now, when the couple is in the 25% bracket, means more IRA assets remain sheltered and will come out at the heirs’ lower rate of, say, 15%, saving 10% of the account from taxation.

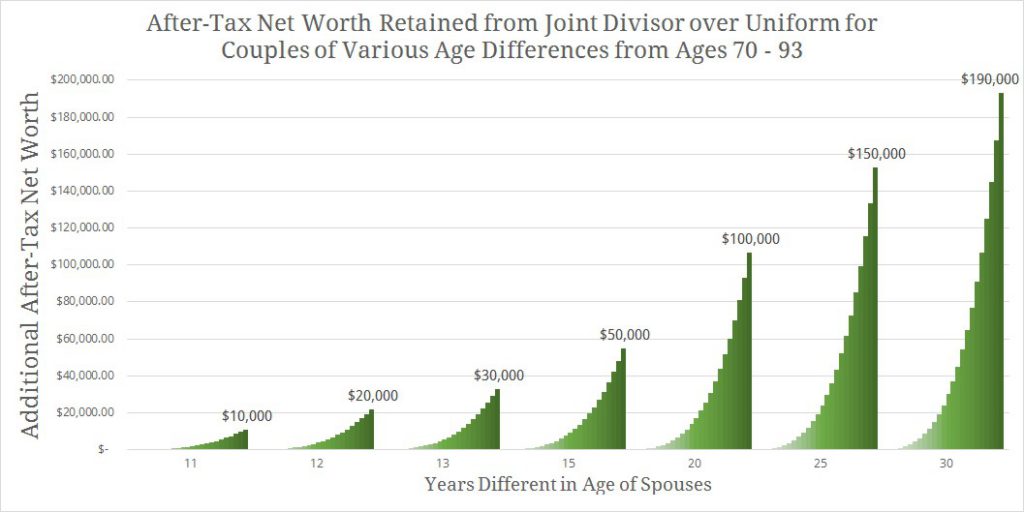

The larger the age gap between spouses, the larger the savings from using the Joint divisor. Here are a few graphs, like the one above, showing the savings from using the Joint divisor for various spousal age differences:

The savings add up quickly, as high as $190,000 or 19.3% of the initial IRA value at age 93 for a couple with a 30-year difference between their ages (ages 70 and 40 in the first year).

If you are a mixed-decade couple, take advantage of the Joint divisor by making your spouse your primary and sole beneficiary for your IRA and use the Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table to find your RMD.

Photo used here under Flickr Creative Commons.